Reference: Conder, E. B., & Lane, J. D. (2021). Overhearing brief negative messages has lasting effects on children’s attitudes toward novel social groups. Child Development, 92(4), e674-e690.

Chances are, you recently had a video call with someone. Maybe you FaceTimed your friend or had a virtual job interview. People use video calls to learn about the world around them and to stay connected. Families introduce their children to video calls to catch up with their out-of-town family members or even to learn a new skill. Research suggests that very young children learn and remember information from a video call, especially when parents participate in the call with them.

But what about video calls where children are not the intended audience? In a recent paper, Drs. Emily Conder and Jonathan Lane investigated whether children’s opinions about a novel social group changed based on information they overheard exchanged between two people. But there was a twist. One person was in the room, and one joined from a video call.

The Lowdown on Previous Research

Their paper was based on a few “givens” – ideas from previous research that paved the way for their set of experiments. First, we know that children are susceptible to messaging about other groups of people. In other words, if children are told that a group of people are ‘bad’, they may develop beliefs that mirror those messages. Second, children are willing to eavesdrop to learn new information. Children can learn everything from names of objects to whether it is advantageous to cheat on a test from overhearing conversations. Conder and Lane therefore sought to combine these ideas and extend them to video calls. Would children develop beliefs about a made-up group of people based on overhearing brief negative messages exchanged via video call? And how would this change with age?

Establishing a Method

In Conder and Lane’s study, 121 children ranging from 3- to 9-years-old were told that they were going to play a fun picture-finding game where they looked for certain targets in an image. While the child was distracted by this game, the experimenter would play a pre-recorded video call from an adult or child caller. This call took one of two paths. In the first, the experimenter receives an unexpected video call and engages in a brief conversation with no negative messages about a social group. We’ve all had a call that looks and sounds like this one: someone calls thinking that we’re not busy, finds out that it’s not a good time, and ends the call. In the second path, the people engaged in the call had a conversation about why a group of people are “bad.” In this conversation, the experimenter mentions to the caller that she’ll be talking about a group of people called “Flurps” or “Gearoos” with the participant. The authors use a novel group, as opposed to a familiar one, to avoid existing biases or preferences that children might have. The caller responds that these people “eat disgusting food, and wear such weird clothes” and that their “language sounds so ugly.” The child is distracted, but as the saying goes, little pitchers have big ears.

What Did Children Learn?

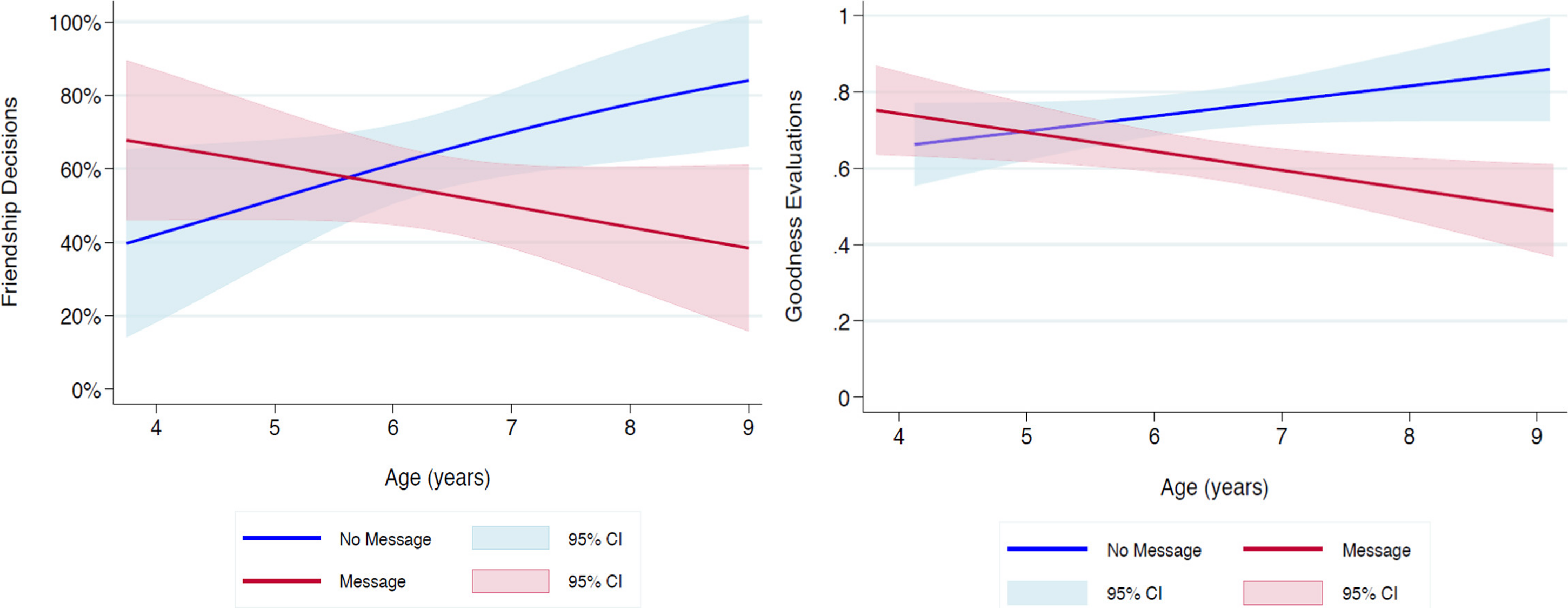

It was now time for the researchers to determine whether children paid attention to the conversation, and whether they used the information contained in the conversation to inform what they believed about Flurps and Gearoos (for simplicity, I’ll use only “Gearoos” to talk about the methods and findings). The researchers asked the children who participated several questions about Gearoo people both immediately after the video call and two weeks later. At each session, they asked if the child would want to be friends with Gearoos and if Gearoos are good people (and how good they are). Children behaved differently depending on their age. 5- and 6- year-olds were equally willing to be friends with Gearoos whether they had heard the negative messages or not. In contrast, 7- to 9- year-olds’ willingness to be friends with Gearoos decreased, but only when they had heard the negative message (if they hadn’t, their willingness to be friends with a Gearoo child actually increased with age). Children behaved similarly when asked about how good Gearoos are. Although 5-year-olds evaluated Gearoos as good whether they had heard the negative message or not, 6- to 9- year-olds who overheard the negative message said that Gearoos were less good than the children who did not.

Left: “Probability of children choosing to be friends with the novel group member, by children’s age. Children overheard a video call in which the caller either made negative claims about a novel social group (red line) or did not (blue line).”

Right: “Evaluation of a novel group’s “goodness,” by participant’s age. Goodness evaluations ranged from 0 (very not good) to 1 (very good). Children overheard a video call in which the caller either made negative claims about a novel social group (red line) or did not (blue line).”

Results are averaged across choices made immediately following the video call and 2 weeks later. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals. Captions and graphs original to paper. (Conder, E. B., & Lane, J. D. (2021). Overhearing brief negative messages has lasting effects on children’s attitudes toward novel social groups. Child Development, 92(4), e674-e690.)

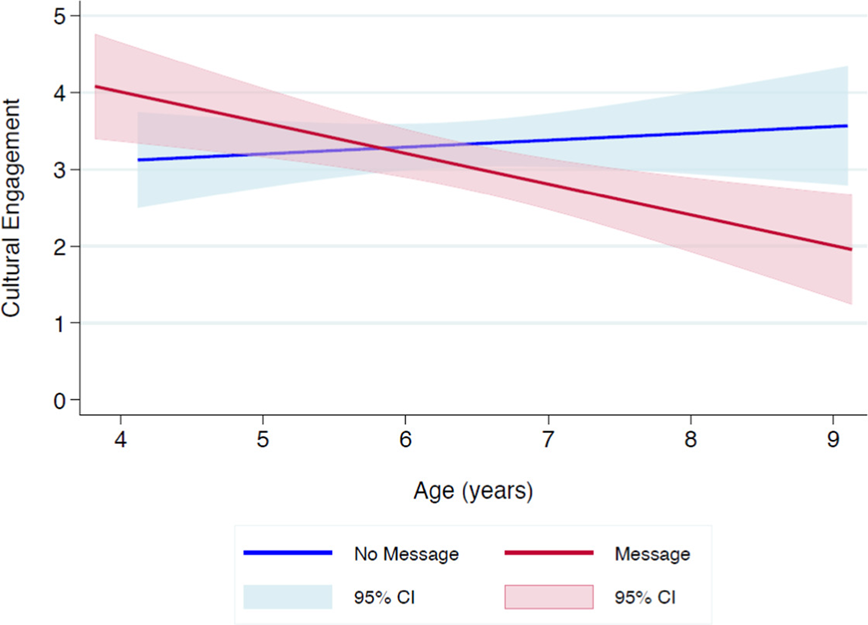

Next, the researchers also explored children’s willingness to engage with Gearoo culture. Conder and Lane didn’t stop at asking about the aspects of culture mentioned directly in the video call (their clothes and their food), but also included three other aspects of cultural identity: playing a Gearoo game, going to a Gearoo party, and learning the Gearoo alphabet. Once again, age and message group mattered. As the age of the participant increased, children’s willingness to engage in various aspects of Gearoo culture increased if they had not heard the negative messages and decreased if they had.

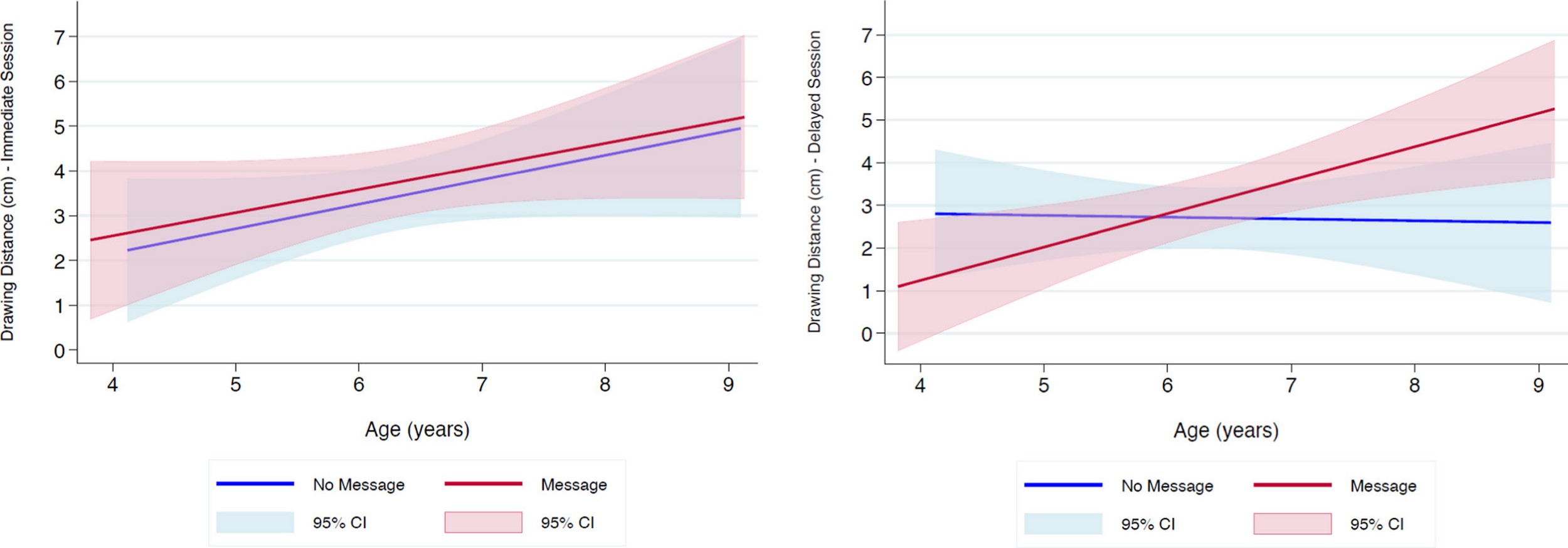

Finally, children were asked to draw themselves with a Gearoo person. This method revealed important insights into children’s mindsets. Older children in the negative messaging group drew themselves further away from the Gearoo person than younger children did, but older children in the neutral group drew themselves closer to the Gearoo person than younger children did. Perhaps most importantly, children did this after the two-week delay, suggesting that their desire for distance grew as their attitudes cemented over time.

What Did We Learn?

The significant findings in Conder and Lane’s paper persisted after two weeks had passed. In the neutral group, oldest children were the most willing of the participants: they indicated that they would be friends with Gearoo people and engage in their culture more than younger children. Yet it was also the older children in the sample that formulated negative opinions about another group of people after overhearing a single brief negative message about that group.

The takeaway here is profound: even in the face of distraction, children as young as 6 can not only overhear information exchanged by people on a video call but also use that information to inform their immediate and later beliefs and behavior. Video calls are an invaluable way to stay in touch. Using the wonders of Zoom, we can catch up about everything from current events to our frustrations and triumphs. But adults should also remember: what we say with kids around may have a larger influence than we think.

[…] recently wrote a cogbite about one of her favorite research articles that found that children learn and remember negative […]

LikeLike