Reference : Romero-Rivas, C., López-Benítez, R., & Rodríguez-Cuadrado, S. (2022). Would you sacrifice yourself to save five lives? Processing a foreign language increases the odds of self-sacrifice in moral dilemmas. Psychological Reports, 125(1), 498-516.

Perceptions around bilingualism are changing fast, and it’s welcome news for the 43% of the world’s population who use two languages on a daily basis. Historically, concerns about dual-language upbringing and its detrimental role in educational achievement were rooted in negative attitudes towards immigration and xenophobia (1). However, contemporary research is uncovering a wealth of cognitive advantages associated with early dual-language acquisition, ranging from improved attention and conflict management to potential safeguards against cognitive decline later in life (2).

It isn’t just children growing up in bilingual households that experience the benefits of bilingualism. Research focusing on ‘late bilinguals’ – individuals who acquire a foreign language later in life – also reap some cognitive rewards (3,4). In our increasingly globalised world, where many people use multiple languages daily, it becomes increasingly important for researchers to delve into questions about how language choices affect decision-making. Language-context morality is becoming even more significant given that more and more companies and political systems have people making world-changing decisions in a language that isn’t their first.

The Moral Foreign Language Effect (M-FLE)

The Foreign Language Effect was first described by Keysar and colleagues in 2012 (5), after finding that the decisions people made varied depending on the language they used to make them. This phenomenon has since been observed across late bilinguals and appears to affect multiple aspects of decision-making. Subsequent research has linked language processing to a variety of behavioral effects, from a reduced aversion to risks when processing dilemmas in a foreign language (6) and decreased bias around responsibility for events when assigning responsibility for causes (7), to an increased willingness to be honest about salaries! (8)

The Moral Foreign Language Effect (M-FLE) is a branch of research specifically focused on explaining why this variation in moral processing occurs, and why reduced emotional reactions are observed when people process moral dilemmas in a foreign language they learn later in life (9). Researchers have ruled out cultural or language-specific factors as underlying causes, as similar findings emerge across various languages and settings (10).

What might cause the M-FLE?

One prominent theory for the M-FLE comes from observations that speaking a foreign language requires significant mental effort. To recall words in a second language, the brain needs to inhibit the primary language to avoid the interference of native words (11). The mental effort involved in this inhibitory process reduces the likelihood of an automatic emotional reaction to the scenario, leading to a more muted emotional response. Another possibility is the sheer vacancy of emotional meaning for a lot of late learners (12). No matter how immersed they become in a second language, if the language was predominantly learned in an academic or an emotionally void scenario as opposed to the home as for many bilinguals, perhaps the language just carries an absence of emotion. Additionally, learning a language later in life may limit access to information about the social and moral norms associated with that culture (13).

Research into the Theory of Mind (the ability to understand others’ perspectives) supports the idea that late language acquisition contributes to reduced emotional response. Bilingual children appear to acquire Theory of Mind earlier than those who only speak one language, and even as adults, they show increased empathy for other people’s pain when using a language other than their native language.

The researchers in this study were able to delve into what might cause varied levels of emotion by looking more closely at the kind of moral decision-making done in each language, and whether these decisions were driven by a feeling of self-distance from the situation, increased empathy for others, or both.

The Study

To investigate the causes of M-FLE, Romero-Rivas and colleagues expanded on previous research (14) by using the “trolley” and “footbridge” moral dilemmas, commonly employed in experimental philosophy to explore moral decision-making and described below.

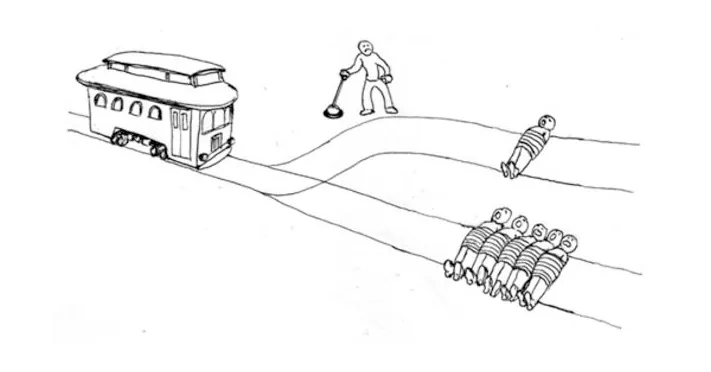

The Trolley Dilemma

In this scenario, participants are asked to imagine there’s a runaway trolley car hurtling down a track. If it continues its course, five people will be hit, but if a lever is pulled to divert it, only one person would be. Participants are asked to imagine they’re standing some distance away, next to the lever and have (only) two options:

- Do nothing, in which case the 5 people will be hit

- Pull the lever and divert the train, hitting one person but saving the other 5.

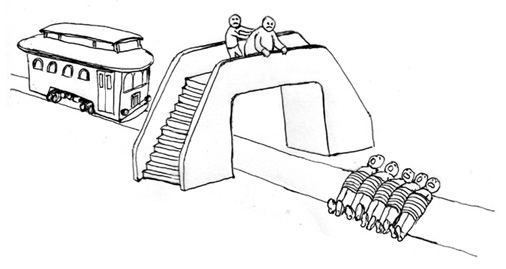

The Footbridge Dilemma

In this scenario, the details are similar to the trolley dilemma described above, except participants are asked to imagine they’re on a footbridge instead of by a lever, and can save the five people by pushing one person off the bridge into the trolley’s path. The only option is whether or not to push the other person and is used as a more emotionally aversive alternative to the trolley dilemma. Because the choice to push someone is a lot more active than passively pulling a lever, meaning participants may feel they’re proactively taking a negative action, a sense of guilt may also play a key role in this scenario.

In Costa’s study on foreign language effects, significantly more people (44%) chose to push the bystander off the bridge to save the others when answering in a foreign language than their native language. This outcome indicates that processing in a foreign language may increase emotional distance and encourage more rational-based decision making.

To assess whether this rationality stemmed from empathy for others or a reduced feeling of personal involvement, research by Romero-Rivas used the same dilemmas as Costa, but added a novel third option to the dilemmas: the chance to self-sacrifice to save the others.

The researchers recruited 300 native Spanish-speaking university students who had learned English as a second language in a formal setting like school, but never lived more than a year in an English-speaking country or spoke it at home. To ensure that any effects observed could be better attributed to language rather than personal variation (as many some people were simply more empathetic via other circumstances), they simultaneously measured the affective and cognitive empathy of participants on the Basic Empathy Scale in Adults (BES-A). This scale measures empathy using three main pillars: emotional contagion (i.e., the social spread of emotional responses), emotional disconnection (a distancing from the situation), and cognitive empathy (i.e., understanding another’s feelings even if you don’t agree). The students were randomly assigned to a group (either the trolley or footbridge dilemma in either Spanish or English) and filled out the BES-A in the same language as the dilemma.

More likely to self-sacrifice

The results showed that participants were more willing to sacrifice themselves (as opposed to sacrificing someone else or doing nothing) when they processed the dilemma in a foreign language. That is, 28.47% of people chose to self-sacrifice when the dilemma was presented in English compared to 17.20% choosing to self-sacrifice when the dilemma was presented in their native Spanish. Interestingly, participants who responded to the BES-A in English had lower affective and cognitive empathy scores than those who responded in Spanish. This apparent contradiction between an increased willingness for self-sacrifice and a lower effect of empathy suggests that processing moral information in a foreign language may reduce emotional involvement while maintaining, or even enhancing, empathy toward others.

Participants were also more likely to sacrifice themselves in the trolley (46.27%) than in the footbridge (45.15%) dilemma, which reflects traditional responses – the footbridge scenario is more emotionally salient. Similarly, with the inclusion of a self-sacrifice option, the increase in people sacrificing themselves on the trolley version might be because of the stronger societal taboo around jumping from a bridge compared to pulling a lever. Alternatively, this outcome could also be related to a lack of social context when thinking in another language. Without having the full social context of a language, making straightforward moral decisions might be easier.

The main takeaway from this research is that the reduced emotional response to moral information when processing in a foreign language vs. native language is more strongly felt about emotions about others. When it comes to emotions related to the self, people are actually more sensitive in a second language than their native.

Future research

To gain a deeper understanding of M-FLE, future research would benefit from investigating different levels of language proficiency, as this study group included participants with varied foreign-language abilities. This variability in language ability makes it difficult to determine whether the outcomes could be influenced by participants with lower foreign language abilities not fully understanding the dilemmas, rather than an increase in empathy.

Additionally, exploring how different language acquisition contexts (e.g., academic programs compared to family immersion) influence the M-FLE could shed more light on whether an emotionally rich language learning experience increases empathy in that language.

Despite these caveats, the study’s findings raise some interesting considerations about how we make moral decisions. It’s significant that the participants in the study had a similar educational background and learned English in an environment that resembles that of many world leaders, who often have to make challenging moral choices in a language that’s not their first. Understanding how bilinguals navigate moral dilemmas can have far-reaching implications on global policy and other high-stakes decisions.

Images : (1) Languages Around the World. Accessed 8.10.23. Link

(2) The Trolley Dilemma. Accessed 8.10.23. Link

(3) The Footbridge Dilemma. Accessed 8.10.23. Link

Additional References

(1) Vicol, S. (2019). The Politics of Bilingualism in the United States: A New Perspective on the Immigration Debate. Stanford University : Humanities and Sciences, 18, 43-49.

(2) Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: consequences for mind and brain. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(4), 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.03.001

(3) Norcross, G. (2020). Is foreign language learning related to cognitive functioning? Cogbites. https://cogbites.org/2020/02/24/is-foreign-language-learning-related-to-cognitive-functioning/

(4) Bak, T. H., Vega-Mendoza, M., Sorace, A. (2014). Never too late? An advantage of tests of auditory attention extends to late bilinguals. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00485

(5) Keysar, B., Hayakawa, S. L., & An, S. G. (2012). The foreign-language effect: Thinking in a foreign tongue reduces decision biases. Psychological Science, 23(6), 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611432178

(6) Costa, A., Foucart, A., Arnon, I., Aparici, M., & Apesteguia, J. (2014). “Piensa” twice: On the foreign language effect in decision making. Cognition, 130(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.010

(7) Díaz-Lago, M., & Matute, H. (2019). Thinking in a Foreign language reduces the causality bias. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 72(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021818755326

(8) Bereby-Meyer, Y., Hayakawa, S., Shalvi, S., Corey, J. D., Costa, A., & Keysar, B. (2018). Honesty speaks a second language. Topics in Cognitive Science, 12(2), 632–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12360

(9) Costa, A., Foucart, A., Hayakawa, S., Aparici, M., Apesteguia, J., Heafner, J., Keysar, B. (2014). Your morals depend on language. PLoS One, 9(4).

(10) Cipolletti, H., McFarlane, S., Weissglass C. (2016). The moral foreign-language effect. Philosophical Psychology, 29, 23–40.

(11) Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingual Language Cognition, 1, 67–81. doi: 10.1017/S1366728998000133

(12) Caldwell-Harris, C. L. (2015). Emotionality Differences Between a Native and Foreign Language: Implications for Everyday Life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(3), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414566268

(13) Geipel, J., Hadjichristidis, C., Surian, L. (2016). Foreign language affects the contribution of intentions and outcomes to moral judgment. Cognition, 154, 34–39.

(14) Wu, Y. J., Liu, Y., Yao, M., Li, X., & Peng, W. (2020). Language contexts modulate instant empathic responses to others’ pain. Psychophysiology, 57(8), Article e13562. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13562