Reference: Holzer, J., Korlat, S., Pelikan, E., Schober, B., Spiel, C., & Lüftenegger, M. (2024). The role of parental self-efficacy regarding parental support for early adolescents’ coping, self-regulated learning, learning self-efficacy and positive emotions. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 44(2), 171–197.

Believing in yourself is important. Often, how much you believe you can do a specific task impacts how well you’ll do that exact task, or if you’ll even do that task at all. This concept is called self-efficacy.

But does believing in yourself impact how others perform in certain situations? This question could be asked across a lot of contexts; however, it’s important to understand how this looks in parent-child relationships. Researcher Julia Holzer and her colleagues at the University of Vienna recently asked just this question: Does how much a parent believes in their ability to support their adolescent child impact how their adolescent learns and feels? To understand the nuances of how they asked and examined this broad question, we first need to understand coping in adolescents and support in parents.

Adolescent coping

When exposed to challenging experiences, adolescents may engage in what is called coping, or means of dealing with these experiences. Coping comes in many flavors, but here we are focusing on problem-focused and emotion-focused coping.

Problem-focused coping involves facing the experience head-on by tackling the situation as a “problem.” This may look like an adolescent problem-solving, or it might look like the adolescent talking themselves through the situation in a positive way. Generally, problem-focused coping is viewed as a positive and healthy means of coping. However, when a situation—such as the COVID-19 pandemic—is out of the adolescent’s control, applying problem-focused coping may come along with behavioral issues; it’s not feasible to problem solve a situation that is completely out of your control. Generally, learning is something within the control of people, so an adolescent exercising problem-focused coping in a learning environment might find this strategy is an adaptive approach.

Emotion-focused coping means you are approaching an experience by managing your feelings about it. An adolescent applying this approach may try to minimize how much they are worrying about a situation or attempt to distract themselves by thinking about or doing other things. Generally, emotion-focused coping is considered maladaptive because it is usually associated with mental health concerns including anxiety and depression; this is because these coping strategies are focused on avoidance strategies, such as distractions or the worries an individual has. However, for uncontrollable situations (like a pandemic), emotion-focused coping might be a helpful way to deal with the context.

Parental support

Parents provide various types of support to their children. The researchers focused on emotional support and instrumental support. When a parent provides their adolescent with emotional support, they are providing care that fosters the well-being of their child, such as empathetic comments or listening. The goal of such support is to promote well-being and help support their adolescent in coping with stressful situations. When a parent provides their adolescent with instrumental support, they are providing care that their adolescent can use to achieve a goal – such as offering help to complete homework. In this way, instrumental support is directly related to the academic outcomes of adolescents.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, parents were an important resource for their adolescents—for both the well-being of these adolescents, as well as their progress in learning (because most adolescents were isolated at home instead of being able to go to school). Despite research before the emergence of COVID-19 showing that parental support was key to adolescent resilience to and coping with adverse experiences, little research examined this phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What did the researchers do?

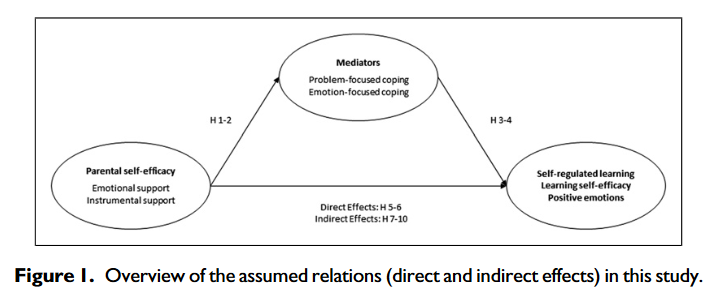

To address this gap in the literature, Holzer et al. (2024) specifically asked how much parents believed they could provide emotional and instrumental support could influence adolescent academic outcomes. They also asked if this proposed relationship was mediated by adolescent problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Specifically, the researchers wondered if how much parents believed they could support their adolescent influenced how their adolescent used coping skills, which subsequently influenced their adolescent’s learning.

Image credit: Holzer et al., 2024

To look at this problem, the researchers asked 263 Austrian adolescents (ages 10-14) and their parents to complete online questionnaires in 2021 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The questionnaires they used for parents were created specifically for this study and focused on their self-efficacy to provide support to their adolescents. The questionnaires for adolescents were pre-existing questionnaires, and looked at problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, self-regulated learning, learning self-efficacy, and positive emotions.

What did they find?

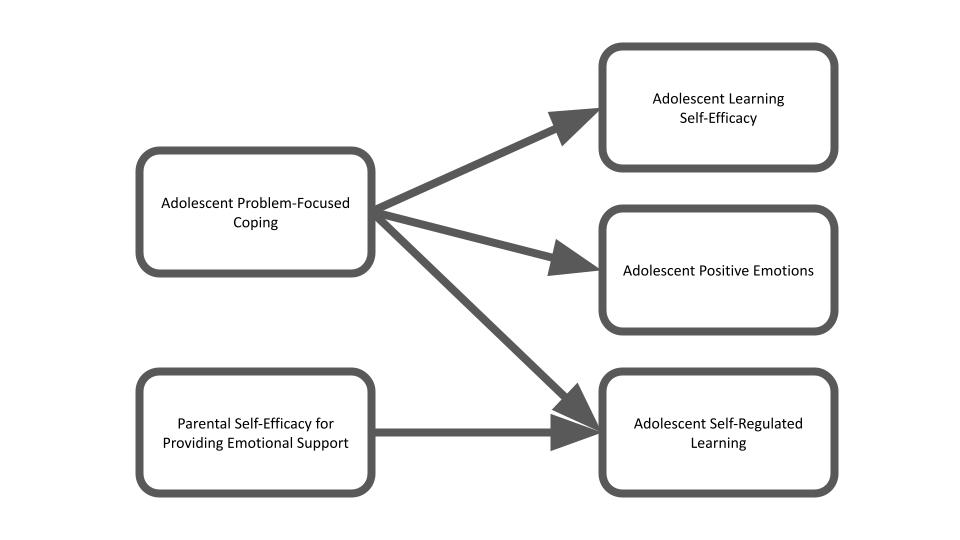

When the authors looked at the direct impact of parental self-efficacy for support on adolescent coping, they found no significant relationship. This outcome means that how much a parent believes in their ability to provide support doesn’t change how much an adolescent uses coping skills. The authors found a similar lack of relationship between the emotion-focused coping of adolescents on aspects of learning: adolescent emotion-focused coping does not change adolescent self-regulated learning, learning self-efficacy, or positive emotions. Furthermore, parental self-efficacy for emotional or instrumental support didn’t change adolescent learning self-efficacy or positive emotions, nor did parental self-efficacy for instrumental support impact adolescent self-regulated learning. Finally, none of the indirect effects explored were found to exist: this means that parental support self-efficacy does not impact adolescent self-regulated learning, learning self-efficacy, or positive emotions via adolescent coping.

Despite these insignificant results, the authors did find a handful of key relationships in the ideas they examined. Adolescent problem-focused coping does indeed positively impact all three adolescent outcomes: self-regulated learning, learning self-efficacy, and positive emotions. Additionally, parental self-efficacy for providing emotional support impacts adolescent self-regulated learning.

As the authors point out, adolescents whose parents report being strong providers of emotional support engage in more regulation of their learning; in contrast, if a parent reported being a strong provider of instrumental support, the adolescent did not engage in managing their learning. Furthermore, when adolescents apply problem-focused coping skills like problem-solving during the COVID-19 pandemic, they tend to use self-regulated learning skills more, show an increase in learning self-efficacy, and demonstrate increased positive emotions.

What these outcomes mean for you

Overall, when it comes to the controllable stressors of school, adolescents who use problem-focused coping feel better about their abilities, feel generally more positive, and can use skills that let them regulate their learning through planning, monitoring, and reflecting. Additionally, the authors state that their results show that using emotion-focused coping—while not necessarily a good thing—isn’t a bad thing either, regardless of whether the situation is controllable or not. If an adolescent has a parent who believes they can provide emotional support, the adolescent likely will feel more supported and capable of regulating their learning, and broadly positive. However, if a parent feels they are better at providing help, the adolescent may not feel they have to put effort into regulating their learning because someone else is doing so.

Taken together, these outcomes suggest that adolescents need problem-focused coping skills to provide for academic success. Additionally, parents should focus on their ability to provide emotional support if they want to improve their adolescent’s academic outcomes and should avoid doing the work for their adolescent.

[…] has already contributed to Cogbites! Her first post explores how parents’ confidence in supporting their adolescents affects how those adolescents […]

LikeLike