Reference: Shtulman, A., & Valcarcel, J. (2012). What happens when learning scientific theories conflicts with people’s intuitions? Science knowledge suppresses but does not supplant earlier intuition. Cognition.

Albertina has always been a curious child, fond of exploring the world and learning about nature – especially plants and animals. From running around her grandparents’ farm, she realized that all the farm animals moved, yet none of the plants in the crops did. She eventually concluded that animals were living beings but plants were not, because plants did not move and so they were more similar to rocks. When starting primary school, Albertina was aghast upon learning that, contrary to what she believed, plants were living beings as well.

Albertina’s story is a great example of how people learn about the world: When people (and children in particular) interact with the world around them, they develop intuitions about how it works. These intuitions – henceforth, naïve theories – span domains such as physics, biology, and psychology. By the time children start their formal education, they already have several naïve theories that can align or run counter to the scientific theories they are taught at school.

Does formal learning ‘eliminate’ previous theories about the world?

One of the goals of formal education is to help people learn accurate scientific theories. Underlying this goal is the assumption that learning an accurate scientific theory replaces or eliminates a previously held (inaccurate) naïve theory. But are naïve theories ever really eliminated? Or do they instead coexist with later acquired scientific theories and continue to influence one’s thinking and behavior? Researchers Shtulman and Valcarcel (2012) explored these possibilities in their work.

Shtulman and Valcarcel’s (2012) research

Shtulman and Valcarcel (2012) tested whether learning about a scientific theory replaces or suppresses a corresponding naïve theory. If learning a scientific theory eliminates the corresponding naïve theory, then the latter should not influence people’s thinking. That is, Albertina’s naïve theory that plants are not living beings should be discarded and no longer influence her thinking from the moment she learns that, by scientific standards, plants are living beings. If, on the other hand, naïve theories are not discarded when scientific theories are acquired, then naïve theories should still influence people’s thinking under some conditions (such as when they are in conflict with the scientific theory, as people will feel divided). In this case, even after learning the correct scientific theory, Albertina’s (erroneous) belief that plants are not living beings could influence how she thinks about plants, and she could still see them as more distinct from animals than they actually are from time to time.

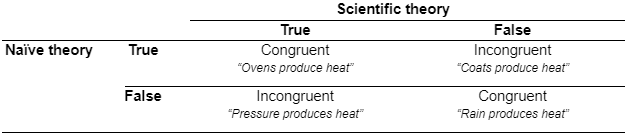

In their study, college undergraduates read a set of statements about natural phenomena (e.g., astronomy, evolution, genetics) and identified, as quickly as possible, whether each statement was true or false according to the scientific theory. The researchers measured their accuracy and response times as a way to see whether naïve theories influenced adults’ reasoning. However, responses following from a naïve theory can align or conflict with the ones in line with the scientific theory. Based on this idea, the statements could be congruent – when both the naïve and the scientific theories suggest the same response (e.g., “Ovens produce heat” is true according to both of them) – or incongruent – when the naïve and the scientific theories suggest opposing responses (e.g., “Coats produce heat” is true according to a naïve theory, but false according to the scientific one). Thus, if scientific theories completely replace naïve theories, adults should be as fast and as accurate to respond whether a statement is true or false regardless of whether the statement is congruent or incongruent. In other words, they would be equally fast and accurate to claim that “Ovens produce heat” is true as they are to claim that “Coats produce heat” is false (see table below for examples).

What did they find?

Participants were faster and more accurate when naïve and scientific theories converged, or suggested the same response (that is, for congruent statements), relative to when the responses suggested by these theories were at odds with one another (that is, for incongruent statements). It did not matter whether the statement was true or false according to the scientific theory – responses were faster and more accurate for both of them when the naïve theory suggested the same (vs. the opposite) response.

People’s exposure to scientific theories is often spread out across time. For example, children learn about fractions before they learn about evolution. Does the timing of learning influence the extent to which naïve and scientific theories conflict? It seems that this timing does matter: The authors found that participants’ greater speed and accuracy for congruent (vs. incongruent) statements was more pronounced for topics whose scientific theory was acquired earlier. In other words, the difference in speed and accuracy between congruent and incongruent depended on when people had typically learned about the scientific theory.

What is the meaning of these findings?

So, does your early developed naïve theory about living things influence your ability to quickly recognize that scientific theories identify plants as living things? Shtulman and Valcarcel’s findings suggest that the later-learned scientific theory suppresses, but does not entirely eliminate, existing naïve theories. That is, people’s early intuitions about the world do not really go away, even after they learn about the science behind it. Instead, naïve theories lay dormant and can still influence how people think, namely when people are pressed for time and cannot recruit more complex, scientific theories.

These results help explain people’s resistance to many scientific theories, suggesting that skepticism may be higher when the scientific theory conflicts with a naïve one developed as people go about experiencing the world. Whenever you find yourself doubting how you believe the world works, think about it carefully and try to parse the conflicting – naive and scientific – theories that you may be considering without even realizing!

Image Credits

Featured Image: Photo by Mikhail Nilov, under Creative Commons License CC0. https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-girl-holding-a-test-tube-while-writing-in-the-notebook-8923370/

Table with Trials: Original, based on Shtulman and Valcarcel’s (2012) Table 2.