Why do people love the things we love? How are natural rewards like food, exercise, and social interaction processed within our brains to be pleasurable? And how do drugs hijack these same processes, oftentimes leading to dependence and substance use disorder? Questions like these have been driving research for decades. Neurobehavioral rodent research has greatly improved our understanding of motivation and the brain’s reward systems, which are essential aspects of human behavior. Here we will discuss the brain’s reward circuitry and a key method used in preclinical research to understand reward motivated behaviors.

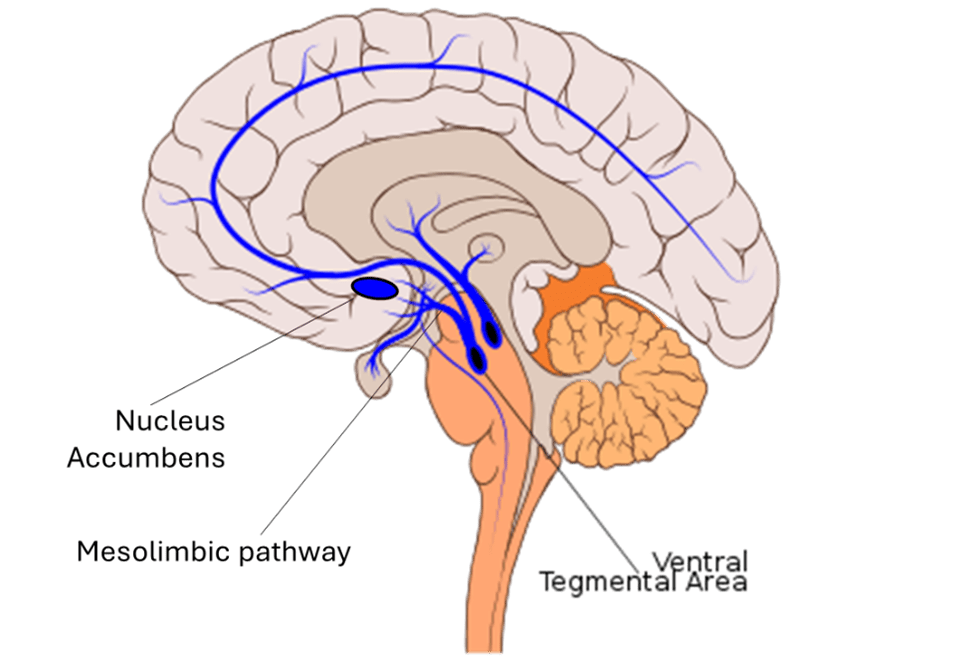

The Mesolimbic Dopamine System

How are pleasurable experiences transmitted within the brain? Canonically viewed as the brain’s reward system, the mesolimbic dopamine system (shown in the figure below) is responsible for conveying and processing pleasurable stimuli. This system relies on the neurotransmitter dopamine to communicate between two key brain regions: the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. Early rodent studies examining the role of the mesolimbic dopamine system have shown that exposure to natural rewards such as cake elicit increased dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (1). Interestingly, exposure to other (less natural) rewards like cocaine have been shown to cause similar dopamine release (2). In this way, drugs and natural rewards engage the same neural circuitry and relay pleasurable experiences through dopaminergic signaling within the mesolimbic system.

Self-Administration: An essential tool in understanding motivated behaviors

So how did researchers gain such a vast understanding of the mesolimbic dopamine system and reward motivated behaviors? The answer lies within a preclinical research technique called self-administration. Such a technique, typically performed in rodents, shapes behavior through use of rewards. In self-administration procedures (shown in the figure below), the animal is placed in a chamber with access to two retractable levers. The animal learns through multiple trials that pressing one of these levers (the active lever) will result in oral or intravenous delivery of some reward (food, sucrose, drug etc.) while pressing the other lever (the inactive lever) results in no reward. When the animal presses the active lever and receives a reward, a cue light located above the lever is illuminated. Through multiple trials and sessions, an association is formed between the cue light and reward, which is important for investigating the role of cues (people, places, and paraphernalia) in drug craving. Decades of research have demonstrated that animals will self-administer various types of rewards such as: food, drugs (cocaine, nicotine, alcohol, opioids, etc.), and even access to social interaction (3). However, the techniques discussed below will focus on self-administration of drugs.

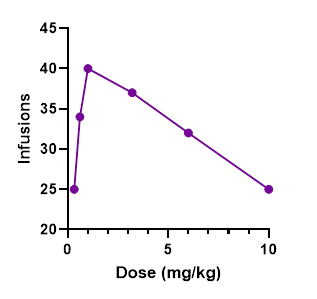

The Basics: Dose-response

Once an animal is trained to self-administer a drug, researchers can begin to alter components of the experiment to observe how the subjects change their response. A common factor that may be changed is drug dosage. By increasing and decreasing drug dose, researchers can develop a dose response curve (shown in the figure below), which is an inverted-U shaped curve detailing how drug intake is altered based on the dose being administered. The x-axis of the curve shows drug dose while the y-axis shows a measure of the animals’ responses (like infusions received). Generally, drug intake will increase with increasing dose until reaching a peak, which is considered the optimally rewarding dose. Past this point, drug intake generally tends to decline as the dosage is too high to be rewarding. Importantly, dose-response curves can be used to detect abuse liability of drugs and test potential compounds that could antagonize, or block, the rewarding effects of addictive drugs, helping to prevent overdose.

The Basics: Schedules of reinforcement

Another factor that may be changed during self-administration is the schedule of reinforcement, which dictates the frequency with which a response is rewarded. Fixed-ratio (FR) schedules of reinforcement are the most common and will result in a reward after a set number of responses. For example, an FR1 means each response is rewarded, while an FR3 means every third response is rewarded, and so on. Normally, animals begin training for drug self-administration on an FR1 schedule, which can be increased (like to an FR3) in subsequent sessions. In a permutation of this approach called the progressive ratio test, the schedule of reinforcement is exponentially increased during the same session. Eventually within the session, an animal may have to press upwards of 100 times for the next reward. At some point, the effort necessary to yield the next reward becomes too high and animals will “give up” and stop responding. This point directly reflects the rewarding efficacy of the substance being self-administered. Researchers have used progressive ratio tests to understand how pretreatment with different compounds or manipulations to neural circuitry affect motivation to receive drugs like cocaine and heroin.

The Basics: Extinction & Drug seeking

Another way researchers experiment with self-administration is to remove the reward. In this process, called extinction, active lever presses no longer result in reward nor the associated cue light. They can then measure how long it takes the animal to extinguish, or stop, responding. Following a period of forced abstinence, animals are placed back into the operant chamber and re-exposed to the cue light, still with no access to the drug. Because animals had learned to associate this cue light with drug availability, responding typically increases when the cue light is re-introduced. This is thought to mimic drug craving and relapse in humans and has been instrumental in highlighting brain areas involved in drug craving, as well as types of stimuli (specific cues, stress, etc.) that increase risk for relapse in people (4).

An important tool in learning about human behavior

Self-administration studies have helped scientists learn so much about motivation and reward. From teasing apart the neural circuitry that drives reward motivated behavior, to testing compounds that can antagonize the effects of addictive drugs, rodent self-administration is a key technique in the field of behavioral neuroscience. As humans, our everyday decisions often involve some level of motivation to receive pleasurable stimuli. We go to work to earn money, we chat with our friends because we enjoy social interaction, we eat dessert because it tastes good, and some people drink or use drugs in a similar pursuit of pleasure. Self-administration procedures have allowed us to model and simplify this behavior in rodents in a manipulatable environment to understand what drives such behavior.

References

(1) Martel, P., & Fantino, M. (1996). Mesolimbic dopaminergic system activity as a function of food reward: a microdialysis study. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 53(1), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(95)00187-5

(2) Hernandez, L., & Hoebel, B. G. (1988). Food reward and cocaine increase extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens as measured by microdialysis. Life Sciences, 42(18), 1705–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(88)90036-7

(3) Lee, S.S., Venniro, M., Shaham, Y. et al. (2024). Operant social self-administration in male CD1 mice. Psychopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-024-06560-6

(4) Myers K.M. & Carlezon W.A. Extinction of drug- and withdrawal-paired cues in animal models: Relevance to the treatment of addiction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 35 (2010) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.011.

Images:

Cover photo- from Jarle Eknes. https://pixabay.com/photos/rat-pet-eat-440987/

Mesolimbic dopamine pathway- adapted from James Neill, under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ventral_tegmental_area.svg