Reference: Faulkner, P., Costabile, A., Imakulata, F., Pandey, N., & Hepsomali, P. (2024). A preliminary examination of gut microbiota and emotion regulation in 2- to 6-year-old children. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 2.

Our society has long recognized the intuitive connection between the stomach and the brain; this link is especially strong in our minds as we conclude the end-of-year period filled with food-related celebrations. For example, we often associate anxiety with an upset stomach or depression with a loss of appetite. When we’re deeply focused on a task, it’s not surprising that we might forget to eat or fail to notice hunger. Most prominently, of course, we often describe people that are hungry as being more irritable, or ‘hangry’. This link between food-related behavior and thinking is well-known, but recent advancements in biomedical technology have led to a deeper investigation into why and how this connection emerges.

Currently, a major candidate mechanism is the gut microbiome, or the ecosystem of trillions of bacteria and microorganisms that live in your gut and help to break down food and absorb nutrients. These gut bacteria are diverse, each playing unique roles, and their relative concentrations are influenced by cognitive or environmental factors like stress. The qualities of the gut microbiome have also been shown to predict changes in cognitive functions and behavior, including issues with emotion regulation and attention.

This bidirectional communication between the gut and the brain is known as the microbiome-gut-brain axis, which has been increasingly linked to the cognitive processing of emotions. For example, in healthy adult women, the concentration of certain gut bacteria has been associated with the balance between emotional suppression, blocking and ignoring emotional experiences, and cognitive reappraisal, or thoughtfully considering emotions before reacting. Importantly, emotion dysregulation, or problems with striking the right balance between these strategies, predicts long-term mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, substance use, and eating disorders.

While the overall diversity of the gut microbiome in infants has been linked to their emotional expression and temperament, it’s crucial that we develop a more nuanced understanding of the microbiome-gut-brain axis in infants, similar to the progress we’ve made in adults and school-aged children. This understanding could allow us to predict and start mitigating negative mental health outcomes as early in life as possible.

How Researchers Explored the Gut-Brain Connection in Young Children

A group of researchers from the United Kingdom started digging into these gut-brain relationships in young children through a study published in August of 2024. made strides toward this goal. They examined the relationships between emotion regulation skills, diet quality, and concentrations of various gut bacteria among 73 children aged 2-6 years (average age = 3.75 years). Mothers collected a stool sample from their child and provided a report of everything the child ate the day before. This procedure allowed researchers to estimate the child’s typical energy and nutrient intake and quantify the child’s gut bacteria concentrations.

Mothers also completed the Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ), which assessed mothers’ perceptions of how frequently their children used positive (adaptive) or negative (maladaptive) emotion regulation strategies. Researchers divided children into two groups based on the prevalence of their maladaptive emotion regulation skills, with those scoring in the higher half placed in one group (36 children) and those scoring in the lower half placed in the other group (37 children). Maladaptive emotion regulation behaviors included maintaining focus on a source of distress, taking their emotions out on things or people unrelated to the stress, behaving aggressively, or making visible efforts to suppress or avoid an emotion.

What the Gut Revealed About Children’s Emotion Regulation

Children reported to show high levels of maladaptive emotion regulation skills had significantly lower alpha diversity (variety) in their gut microbiomes compared to children with lower levels of maladaptive emotion regulation skills. This outcome means that they had fewer unique species of gut bacteria and that the densities of the existing gut bacteria were uneven. Other work has also shown that a more gut microbiome diversity is linked to less emotional suppression in adults and more positive emotional expression in toddlers, both signs of good emotion regulation.

To better understand these differences in microbiome diversity, the researchers compared specific gut bacteria and vitamins. Results showed that children with more maladaptive emotion regulation skills had:

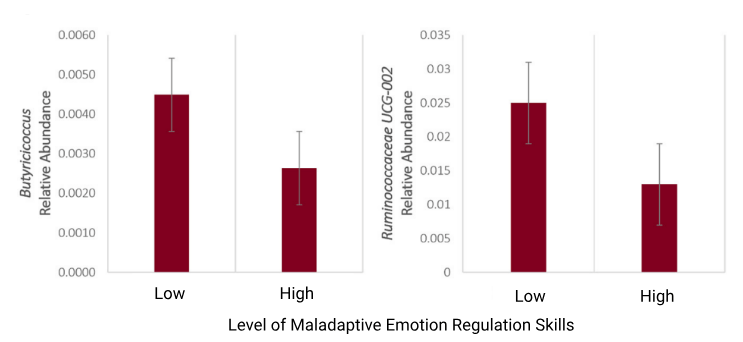

- Significantly lower levels of the gut bacteria for colon health: These bacteria, called Butyricicoccus and Odoribacter (see the figure below) help strengthen cells in the colon’s membrane, preventing inflammation. Low levels of these bacteria have previously been linked to generalized anxiety, obsessive compulsive, and depressive disorders.

- Slightly lower levels of the gut bacteria for processing sources of energy: This bacterium called Ruminococcaceae is involved in how cells get and use energy sources like glucose. Problems with this gut bacteria have been linked to mental health disorders because glucose plays a big role in making neurotransmitters like glutamate, an excitatory ‘on-switch’ for brain pathways, and gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory ‘off-switch’, and serotonin, a major player in mood-regulation.

- Significantly lower production of multiple B vitamins: These vitamins are linked to regulating brain inflammation, making lipids (fats) used to structure the brain, and building neurotransmitters. Changes to the gut’s production of these vitamins can directly influence the brain’s functioning, and have been linked to conditions like autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and mood disorders (like bipolar disorder or depression).

To summarize, more negative emotion regulation habits were associated with (1) lower levels of gut bacteria important for digestion, as well as (2) reduced levels of gut bacteria involved in energy processing and (3) lower B-vitamin production in the gut, both of which are directly linked to brain function.

What This All Means

Overall, these results align with existing research on the microbiome gut-brain-axis in adults and expand this understanding to young children. Lower levels of diversity in the gut microbiome, lower amounts of specific beneficial bacteria, and decreased production of certain vitamins were all associated with more maladaptive emotion regulation behaviors. These outcomes reinforce the idea that gut health is tied to emotional health, even from a young age, and suggest that monitoring gut health could help predict short-term emotional challenges and long-term mental health risks.

However, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The study’s sample size of 73 kids is relatively small for this type of research, and the data on diet and emotion regulation came from parental reports, which might not be entirely accurate. Future studies with larger, more diverse samples that follow kids over time could provide stronger evidence of whether early emotion regulation skills predict long-term mental health like the authors suggested.

Despite these limitations, this study takes important steps toward understanding how the gut-brain axis plays a role in emotional processing throughout life. It seems that, at any age, humans aren’t just “thinking with their stomachs”—they’re also feeling with them. To truly understand the complexities of our emotions, we need to keep the gut in mind, too.

With all this new information in mind, what steps can you take to support gut health for yourself and your family, knowing its potential impact on emotional well-being? Small changes, like adding gut-friendly foods to the diet, could help lay the foundation for better emotion regulation and long-term mental health.