Guest post by Colin McArdle

Have you ever wondered why every person experiences the world differently? Why certain memories stick with you while others fade away, or why a specific taste or smell can transport you back in time? These unique experiences shape how our brains adapt, helping us learn, grow, and respond to the world around us. Maybe you’ve met someone with an intense fear of something that seems insignificant to you—this, too, is shaped by how their brain processes and stores experiences. This ability of the brain to constantly change and adapt based on what we encounter is driven by a fascinating process called synaptic plasticity, which acts as the foundation for how our brains—and our behaviors—evolve over time.

The Synapses – Where Neurons Talk to Each Other

It’s Saturday afternoon. You’re at home, watching the summer Olympics, just in time to see the U.S. track relay team. The race begins as Runner A is only neck-and-neck with their competitors. You watch Runner A sprinting, moving closer to their teammate, Runner B, who is waiting for their signal to start their part of the race. Holding your breath, you watch nervously as both runners execute a flawless exchange of the baton, allowing their team to take the lead and finish first. You burst out in excitement as your country just took the gold!

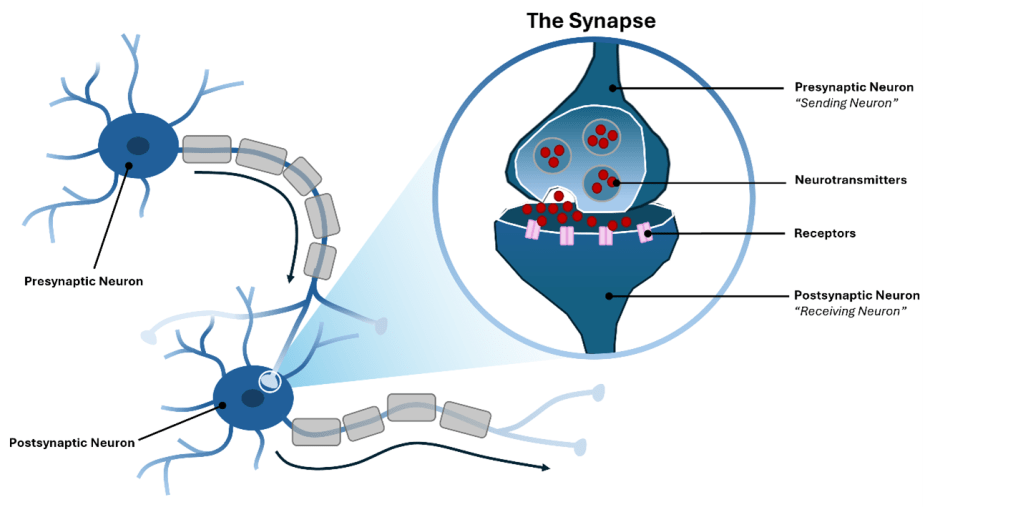

But here’s the twist: this isn’t just about sports. It’s about how your brain operates with the same level of coordination and efficiency. Within your brain, countless neurons work together, passing signals at connection points called synapses, much like the handoff between runners in a relay race. This connection where communication occurs is known as a synapse. Your brain is made up of approximately 86 billion neurons and each of those neurons can make up to a thousand synapses with their neighboring neurons. Grab that calculator because that’s about 100 TRILLION synapses in a human brain! For a synapse to function properly, it relies on three essential components: the presynaptic neuron (“the sending neuron”), neurotransmitters, and the postsynaptic neuron (“the receiving neuron”). Communication starts when the presynaptic neuron sends out small chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters. Think back to the relay team: the presynaptic neuron is like Runner A, passing the baton (the neurotransmitters) to their teammate.

On the receiving end of this “handoff” is the postsynaptic neuron, much like Runner B, who waits for the baton before sprinting into action. In the brain, the postsynaptic neuron contains specialized receptors on the surface. These receptors bind to the neurotransmitters, like Runner B grabbing the baton as a cue to start running. Once the neurotransmitters bind, the postsynaptic neuron now has the signal to begin communicating with its neighboring neuron (1).

Now, zoom out and imagine this process scaled up to the trillions of synapses in the human brain. The question arises: how exactly does a synapse know when to change its function, and how does this change happen on a microscopic level in the brain?

Plasticity – Remodeling Communication Between Neurons

Imagine it’s the following Monday after watching the U.S. relay team take the gold. As you walk to school, you decide to take a dirt path that gets you to your destination in 15 minutes. Over the next week, a few classmates join you, and the dirt path becomes a little wider. Now, imagine jumping forward five years: after countless feet have trodden this route, you’re the town decides to pave over it to create a permanent road in your community.

But what if, that same Monday morning, you’d chosen not take a different dirt path because it was unsafe or much longer, taking 45 minutes to get to school? What would happen to this unused path? Over time, grass, weeds, or bushes would grow over it. Fast forward another 5 years, and the once visible dirt path may no longer be recognizable.

This concept of well-worn and overgrown paths isn’t just a poetic metaphor, like Robert Frost’s “two roads diverging in a yellow wood”. It also mirrors how the brain works. Synapses – connections between neurons – can change their function based how often they are used, a process called synaptic plasticity. — The term “plastic” refers to the brain’s remarkable ability to adapt based on activity.

Synaptic plasticity allows the brain to strengthen or weaken connections depending on their usage. This occurs through two distinct mechanisms: long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). LTP strengthens frequently used synapses, much like the dirt path that becomes a paved road. LTD, on the other hand, weakens unused synapses, much like the overgrown path that fades away.

During LTP, synapses that are more active or frequently used begin to gain more receptors on the postsynaptic neuron. These extra receptors strengthen the synapse’s response, increasing the likelihood that that synapse will remain functional in the brain. During LTD, the opposite occurs. Less active synapses lose receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, leading to weaker responses and a higher chance of becoming silenced and non-functional (2, 3). How does this relate to Robert Frost’s metaphor? LTP is like the chosen path that gradually transforms into paved road through frequent use. On the contrary, LTD is like the the neglected path that becomes overgrown with shrubs. Although Frost was not a neuroscientist, his imagery helps us visualize how the brain decides which connections to strengthen and which to let fade. Human behavior’s ability to make big adaptations depends on small, precise changes in the brain. Synaptic plasticity is the persistent process that ensures optimal function, maintaining a delicate balance between LTP and LTD. In a healthy brain, this balance allows for of the right number of efficient synapses. However, when this balance is disrupted, it can result in many negative effects that can underlie numerous brain disorders.

Through synaptic plasticity, our experiences shape the way neurons communicate, altering the strength of synapses and enabling behavioral adaptations. This dynamic process is why each of us perceive and respond to the world in a unique way. As you read this blog, your brain is adapting and shaping your individual human experience.

Colin is a neuroscience PhD student at Wake Forest University. His research focuses on the role of inhibitory GABAergic receptors in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. Outside of the lab, Colin enjoys cooking, crafting, and DIY interior design projects.

References

- Südhof, T. C. (2021). The cell biology of synapse formation. Journal of Cell Biology, 220(7), e202103052.

- Citri, A., & Malenka, R. C. (2008). Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), 18-41.

- Faust, T. E., Gunner, G., & Schafer, D. P. (2021). Mechanisms governing activity-dependent synaptic pruning in the developing mammalian CNS. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 22(11), 657-673.

[…] Colin is a neuroscience PhD student at Wake Forest University. His research focuses on the role of inhibitory GABAergic receptors in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. Outside of the lab, Colin enjoys cooking, crafting, and DIY interior design projects. He previously contributed posts for cogbites entitled, “Prescribing a Cup of Joe for Alzheimer’s Disease” and “Synaptic Plasticity: Small Changes Make Big Impacts.“ […]

LikeLike

[…] Colin’s research focuses on the preclinical mechanisms driving synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease and on therapeutic approaches to prevent or reverse this damage. He’s also a returning Cogbites contributor—you may have read his posts on topics such as how GABA can be both calming and exciting, whether coffee could be prescribed for Alzheimer’s, and the big impacts of small synaptic changes. […]

LikeLike