Reference: Sparrow, B., Liu, L., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science.

Navigating the world in the digital age

The world around us is so complex that it is virtually impossible to learn everything that there is to know. Imagine being a world-class physicist and a history buff simultaneously, and juggling all of that while having a successful career in computer science. Feels impossible, right? Well, that is probably because it is! But communities and societies have found ways to circumvent the limitations of the individuals they are composed of. How? Through the development of and reliance on transactive memory systems.

Transactive memory systems refer to shared information storage (including people or objects) that helps overcome the limits of personal memory. Communities have learned that, by dividing the knowledge that they possess across its members (instead of everyone having to learn everything), they can maximize the amount of things they know. No single individual knows everything the community knows, but that is not a problem as long as they can lean on other community members when knowledge or information that they do not possess is required.

Over time, humans have developed other external repositories (besides community members) for information that they are incapable of learning themselves, such as writing systems. Recent technological developments have led to the creation of the internet, which makes a plethora of information effortlessly accessible. The internet constitutes a powerful transactive memory system, in that we can access virtually unlimited information easily, at any time.

What changes does this bring about in human cognition? Betsy Sparrow and her collaborators (2011) explored this question.

The internet is highly salient in people’s minds

Sparrow and collaborators (2011) tested the role of the internet in shaping people’s cognitive systems. Among other things, they explored the accessibility of internet-related terms, and when and why people memorize information, as opposed to its location.

In one experiment, they sought to explore whether people naturally think about the internet when they experience a need for knowledge (like they would bring others in their community in early human societies). Put differently, if the internet is considered as a natural reservoir for knowledge that people do not possess, is its presence in people’s minds stronger when people are exposed to things they do not know?

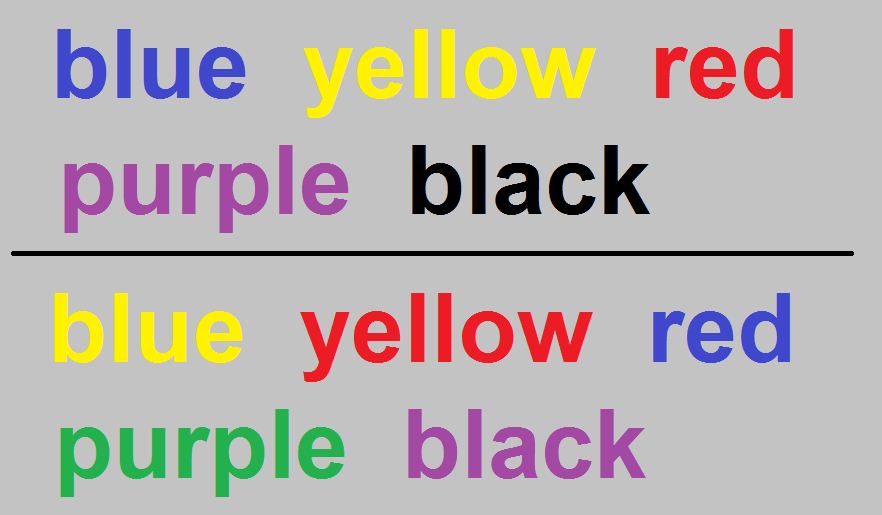

To explore this idea, participants first answered easy and difficult trivia questions in two separate blocks. After each block, they performed a modified Stroop task. In a Stroop task (see examples below), participants must name the color a word is written in while ignoring what the word itself says. If participants are shown the word “blue” written in a red font, they must answer red, for example. This is more difficult than answering red when the word reads “red”. That is because reading words is an automatic task and will thus interfere with the explicit color naming that takes place at the same time. When the word and the font color do not match, interference is higher, and participants are less accurate in color naming and/or take longer to answer (i.e., higher response latencies). This effect is more pronounced if the words participants are shown are active (or easily accessible) in their minds.

Building on this idea, the authors asked participants to name the color (red or blue) of words related or unrelated to the internet. Rather than capturing interference effects based on color congruency, they were interested in exploring these effects as proxies for the cognitive accessibility of internet-related concepts. The authors expected more interference for internet-related (vs. -unrelated) words, especially after participants answered a block of difficult trivia questions. This was because these questions would instigate a need for knowledge in participants, increasing the accessibility of words that could quench it – such as internet-related ones.

Example trials in a classic Stroop task. The words above the black line constitute congruent trials – in that the word written and the color it is written in match. The words below the black line are examples of incongruent trials, where there is interference between the color to name and the word written.

The authors expected internet-related words to interfere with color naming more than unrelated words when participants experienced a need for knowledge because, in these conditions, they should be more attentive to sources of knowledge (which presumably the internet is). As predicted, the latency of the color-naming responses was generally higher for internet-related terms relative to general terms. But this conflict was not independent of the questions participants answered before the task: In fact, the difference in latencies between internet-related and -unrelated words was larger after participants answered difficult questions (relative to easy ones; 818 ms vs. 638 ms, respectively, as opposed to 614 ms vs. 584 ms for internet-unrelated terms).

All in all, this experiment showed that when people are searching for answers they do not possess (e.g., to difficult trivia questions), that makes concepts associated with where to find that information (e.g., internet-related ones) more salient in their minds, which in turn leads to interference in other tasks.

People are strategic in how they recall information and online sources

In another experiment, they examined when and what information individuals memorized based on their expectations about the sources where it was stored. People can either memorize information or focus on where to find it. It is logical for people to memorize the information itself if they have no other place to obtain it later, but they could focus on the source if they expect it to be available instead.

In the experiment itself, participants typed sentences on a computer, which then returned an additional message. Participants saw three different messages, with a third of the sentences being allocated to each: that the sentence they typed had been a) saved, b) saved in a specific folder, or c) erased. Then, participants underwent a recognition test, where half of the sentences had been presented before, while the remainder corresponded to slightly modified sentences (and were therefore new). Participants had to answer whether they had seen the sentence before or not and whether it had been erased or saved. Performance on these can capture whether participants accurately registered the information in question and/or its sources.

In line with the predictions outlined above, memory performance (for the sentences) was better when individuals believed they would not have access to the information later – that is, for erased sentences (proportion = .93), relative to saved (.88) and saved-in-a-folder (.85) ones. At the same time, and also in line with what would be expected, the reverse was found for performance regarding whether the sentences had been saved or erased. That is, participants were more accurate for sentences that were saved (generically – .61 – or in a folder – .66) than they were for those that were erased (.51).

These findings reveal that information unavailable in the future is better remembered, while memory for the source is reinforced for externally accessible information. That replicates how societies learned to cope with the vast amount of information to-be-learned, such that, even if one does not need to hold a specific share of the knowledge the community possess, they still need to know where to access it – or who possesses it – in case they need it in the future.

Thinking about the future: The advent of Artificial Intelligence

Sparrow and collaborators (2011) showed that the internet is highly salient in people’s minds as an external source of information (like other community members were back in the day), judging by the fact that words associated with it are more accessible when participants experience a need for knowledge. Importantly, people adjust the way they interact with this information (and their memorization strategies, specifically) accordingly: Focusing on the location or on the information itself based on whether the former is expected to be accessible in the future or not.

Does this still matter now, provided that the internet is an ever-present force? The answer is definitely yes, because, as internet-related technologies evolve (such as artificial intelligence and large language models), the changes these bring about to cognition will only deepen. That is, Sparrow and collaborators’ (2011) results become ever more true. These concepts are bound to become more salient in people’s minds the more they are ubiquitous, and their presence will influence how people engage with and learn information (namely by memorizing more and more the source, instead of the content itself). It is inevitable that many aspects of society, from public policy to education practices, change as well in order to align with these modified cognitive processes.

Image credits:

Featured image: Photo by rawpixel.com, under Creative Commons License CC0. https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1449171

Stroop task examples: Photo by Xiaozhu89, under Creative Commons License Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. This is a direct copy of the original. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/f/fe/Stroop_Test_2.jpg