Guest post by Colin McArdle

The brain is like a busy city, constantly buzzing with signals sent by tiny chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. These messengers—like dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate—each play different roles to keep the brain running smoothly.

One of the most important neurotransmitters is GABA (short for gamma-aminobutyric acid). GABA is best known as the brain’s “brake pedal”—it helps slow things down, reduce stress, support sleep, and prevent overactivity. Without enough GABA, the brain can become too revved up, leading to anxiety, seizures, or other problems.

So far, so good. But here’s the twist: scientists discovered that GABA isn’t always calming. In fact, early in brain development, GABA actually excites brain cells—it plays for the other team! How is this possible?

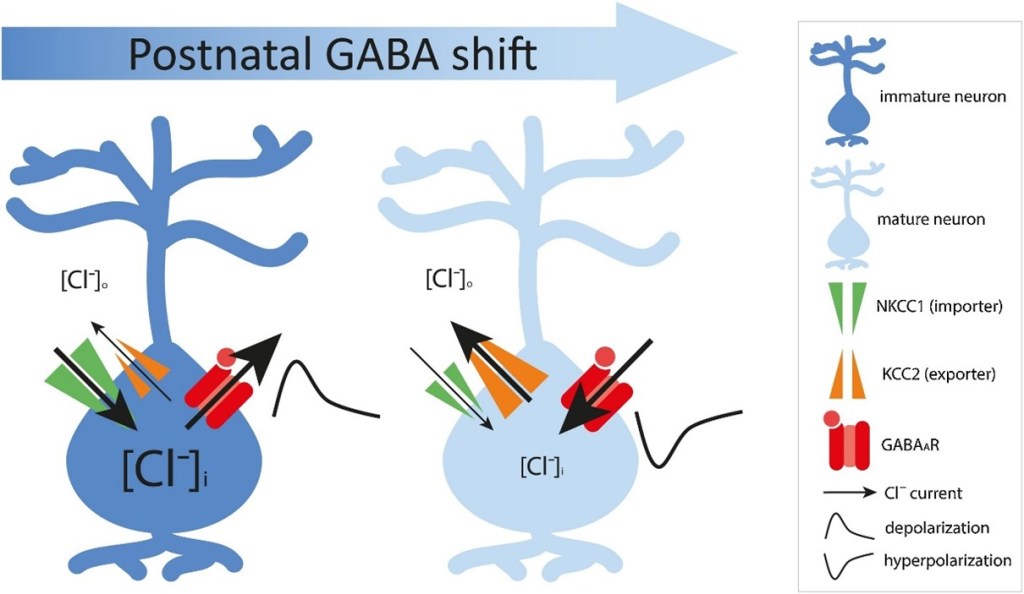

Image from Peerboom & Wierenga (2021).

The GABA Switch: A Traffic Light for Brain Signals

This surprising role reversal is called the GABA switch. Early in life, GABA acts more like a “green light”, encouraging brain cells to fire, grow, and form connections. As the brain matures, GABA flips to a “red light” role, putting the brakes on activity to maintain balance. This switch is essential for healthy brain development, like changing traffic rules as a city grows to avoid chaos.

How Did Scientists Discover This?

Back in 1978, scientists studied spinal cord cells grown in a dish. During early and later stages of development, researchers used electrodes to record the levels of electrical activity as an indicator of how active or inactive these spinal cord cells were. In immature cells, GABA increased electrical activity: surprising researchers by acting like a “go” signal. In mature cells, GABA did the opposite: it decreased activity, confirming its usual calming role (1). Later, in 1989, another study looked at live rats. During the first week after birth, GABA excited brain cells. But after the second week, it switched to calming them down (2). These early studies showed that GABA doesn’t always behave the way scientists expected.

So What Causes the Switch?

The answer lies in tiny particles called chloride ions (Cl⁻) and the transporters that move them in and out of brain cells. In young neurons (i.e., in early brain development), a transporter called NKCC1 pumps chloride into the cell. When GABA binds to its receptor, chloride flows out, making the neuron more active. So, GABA acts as an excitatory signal. In mature neurons, another transporter called KCC2 takes over. It pumps chloride out of the cell, lowering internal levels. Now, when GABA binds, chloride flows in, calming the neuron down. GABA becomes inhibitory again. It’s all about the direction chloride ions move—that’s what flips GABA’s role (3).

Why the GABA Switch Matters

This GABA switch helps build the brain’s foundation: It kickstarts brain development, helping neurons migrate, connect, and sync up. Later, it stabilizes brain activity, supporting focus, memory, and sensory processing. When the GABA switch doesn’t happen properly, it can lead to neurological conditions like epilepsy, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and various substance use disorders. Understanding how this switch works—and what happens when it doesn’t—could unlock new treatments for brain disorders.

Final Thoughts

GABA might seem like a one-trick pony—just a calming brake pedal—but early in life, it’s also the accelerator. This chemical’s ability to “play for both teams” shows just how flexible and fascinating our brains truly are.

Colin is a neuroscience PhD student at Wake Forest University. His research focuses on the role of inhibitory GABAergic receptors in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. Outside of the lab, Colin enjoys cooking, crafting, and DIY interior design projects. He previously contributed posts for cogbites entitled, “Prescribing a Cup of Joe for Alzheimer’s Disease” and “Synaptic Plasticity: Small Changes Make Big Impacts.“

References:

(1) Obata K, Oide M, Tanaka H. Excitatory and inhibitory actions of GABA and glycine on embryonic chick spinal neurons in culture. Brain Res. 1978 Apr 7;144(1):179-84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90447-x. PMID: 638760.

(2) Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaiarsa JL. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1989 Sep;416:303-25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. PMID: 2575165; PMCID: PMC1189216.

(3) Rivera, C., Voipio, J., Payne, J. et al. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature 397, 251–255 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/16697

[…] He’s also a returning Cogbites contributor—you may have read his posts on topics such as how GABA can be both calming and exciting, whether coffee could be prescribed for Alzheimer’s, and the big impacts of small synaptic […]

LikeLike