Guest post by Colin McArdle

Primary References:

Steward, O., & Levy, W. B. (1982). Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. Journal of Neuroscience, 2(3), 284-291.

Torre, E. R., & Steward, O. (1992). Demonstration of local protein synthesis within dendrites using a new cell culture system that permits the isolation of living axons and dendrites from their cell bodies. Journal of Neuroscience, 12(3), 762-772.

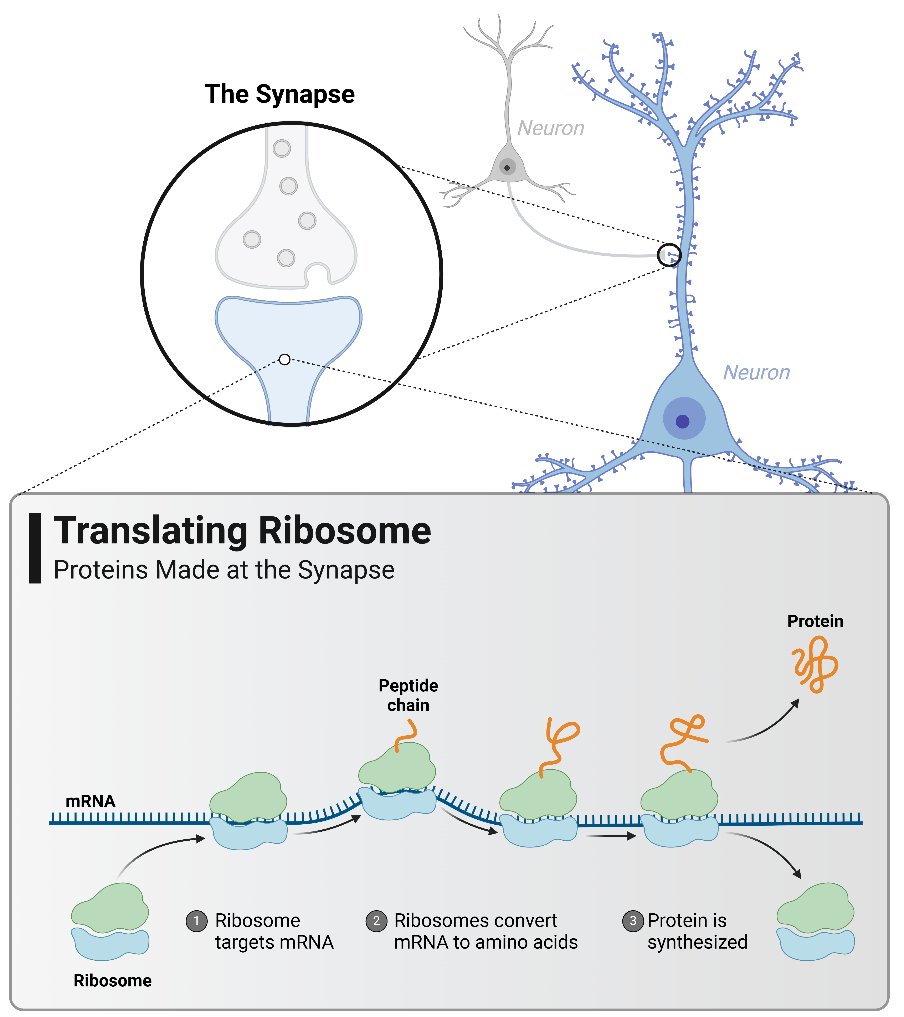

Flashback: You’re back in high school attentively listening to your biology teacher’s lesson on the different parts of the cell. Aside from the nucleus as the master control center and the mitochondria being coined as “the powerhouse of the cell”, you remember that ribosomes are responsible for creating new proteins from messenger RNAs (mRNA) through protein synthesis, formally known as “translation”. When we relay this concept of translation into the context of the brain, neuroscientists were initially under the impression that protein synthesis occurred only in the cell body of neurons, or the soma, and that these newly created proteins would then venture off into different parts of the neuron to perform their niche functions. Sounds straightforward, right? But what if I told you there’s more to the story of protein synthesis? Over decades of research, scientists began to question the long-held idea that protein synthesis happens only in the soma of neurons. A new idea emerged from this research showing that protein synthesis can also occur within neuronal processes – dendrites and axons – through a process called local protein synthesis.

Image created in Biorender.com

What does it mean when proteins are synthesized “locally”? This means that dendrites and axons can convert mRNAs to proteins, independently from the soma. Distant parts of the neuron no longer have to wait for the soma to ship out critical proteins they need. In other words, proteins can be locally sourced within the dendrites and axons!

So how did neuroscientists finally land on the idea that local protein synthesis happens in neurons? Two initial studies – the first conducted at John’s Hopkins University in 1965 by David Bodian and the second at the University of Virginia in 1982 by Drs. Oswald Steward & William Levy – were the first to notice that ribosomes were located not only in the soma, but in dendrites and axons. These studies showed that dendrites and axons had the machinery for protein synthesis—but was it actually functional?

Several studies were successfully able to answer this question. One pivotal study conducted at the University of Virginia in 1992 by Drs. Enrique Torre and Oswald Steward first cut and isolated dendrites from the rest of the neuron. Even after physical separation from the soma, the results from this study showed that dendrites were still successfully capable of performing protein synthesis. Along with several other supporting studies showing that proteins can be assembled far away from the soma, it was then made clear that neurons could undergo protein synthesis throughout all parts of the neuron.

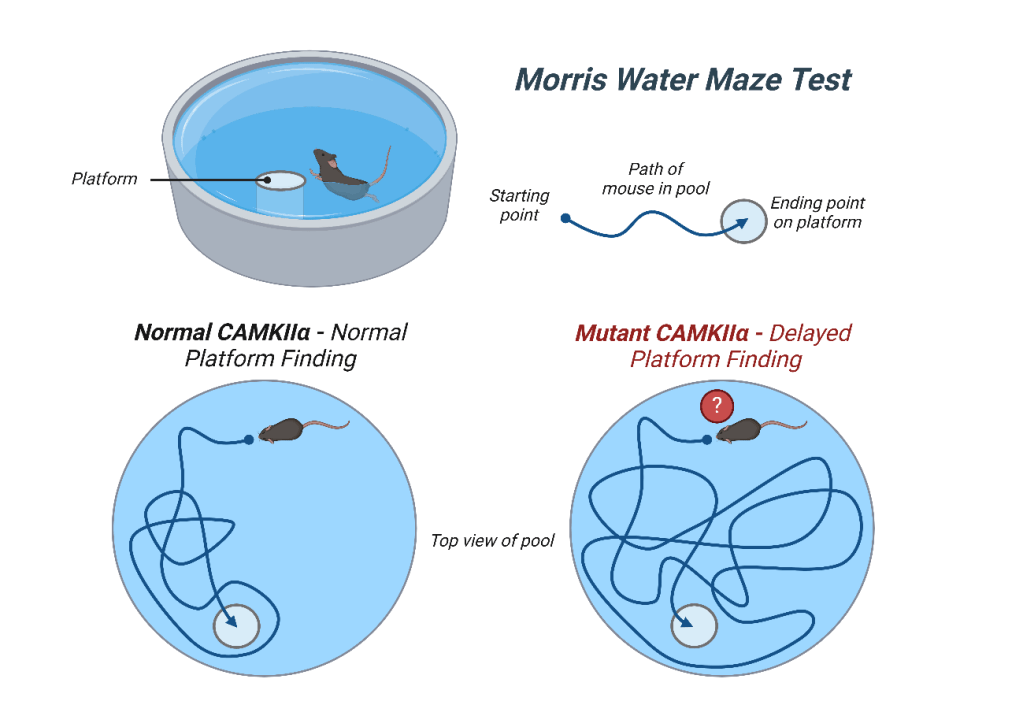

The studies we just discussed showed how proteins can be made in various parts of a neuron, but what does this mean on the grand scale of human behavior? Could local protein synthesis be a critical component in forming and storing new memories? A study conducted in 2002 at the University of California San Diego by Dr. Stephan Miller and colleagues answered this question by looking at the effects of locally synthesized protein in dendrites and how it affected memory in mice. This protein of interest – calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα (CAMKIIα) – is a located and locally synthesized in neuronal dendrites and is highly important in allowing neurons to boost & potentiate their communication. What was so interesting about this study was that the researchers in this group were able to create a “mutated form” of CAMKIIα in a living mouse’s brain such that the neurons could no longer synthesize the CAMKIIα protein far out in the dendrites, but only in the soma.

Image rendered from Miller et al., 2022. Neuron., and created in Biorender.com

So what happens when protein synthesis is stuck in the soma? How does that affect a mouse’s ability to remember? These researchers decided to use a rodent behavioral test known as the Morris Water Maze which tests a mouse’s ability to encode and recall spatial memories. A mouse is placed in pool of cloudy water and must swim and find a hidden escape platform by following several visual cues located around the pool. With the healthy, control mice that had an “unmutated” form of CAMKIIα, they were easily able to find the escape platform in a timely fashion. But mice with the mutated form of CAMKIIα consistently struggled to find the platform, even after multiple attempts (1). The findings from this study not only supported the importance of local protein synthesis in aiding brain function, but also it’s vital role in allowing our brains to properly encode and recall memories!

The ability for humans to interact with their environment is highly dependent on small, molecular changes that occur within the brain. Tiny changes within just a few neurons can set off a chain of events that help us adapt our behavior to new situations. The studies on local protein synthesis in neurons highlight a key example of how nanoscale changes within brain cells affect our ability to performs behaviors such as learning and memory recall. Although once considered ‘unconventional,’ these groundbreaking studies revealed a new way the brain creates proteins—boosting communication between neurons and supporting memory consolidation and recall.

Additional Reference:

(1) Miller, S., Yasuda, M., Coats, J. K., Jones, Y., Martone, M. E., & Mayford, M. (2002). Disruption of dendritic translation of CaMKIIα impairs stabilization of synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. Neuron, 36(3), 507-519.

Colin is a neuroscience PhD student at Wake Forest University. His research focuses on the role of inhibitory GABAergic receptors in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. Outside of the lab, Colin enjoys cooking, crafting, and DIY interior design projects. You can learn more about Colin via this interview post!