Kocharian A, Redish AD, Rothwell PE. (2025) Individual differences in decision-making shape how mesolimbic dopamine regulates choice confidence and change-of-mind. Nature Neuroscience.

Decisions, decisions…which areas of the brain are active during decision-making?

We’re faced with a series of decisions each day – what to have for lunch, which route to take home, or what to buy at the grocery store. Your brain evaluates the situation and uses your past experiences to select the best option. The decision-making process doesn’t stop once you’ve selected a choice. Your brain weighs the consequences of your decision and looks for better alternatives, which is why during grocery shopping, you may go back and grab the cookies you initially skipped or abandon one check-out line for another that’s moving much faster. Changing your mind can often be better in the long run.

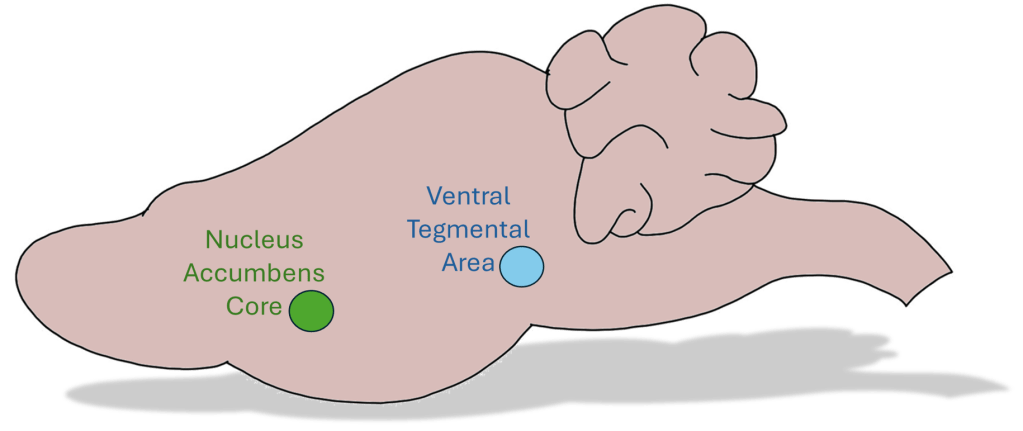

The Nucleus Accumbens Core and the Ventral Tegmental Area (NAc and VTA) are regions of the brain that are important for reward processing, and they work together in the decision-making process. Specifically, release of dopamine, a chemical messenger, in these areas plays a key role. But does dopamine give us any information about when we change our minds? This is what scientists at the University of Minnesota Medical School are working to uncover.

This diagram of a mouse brain shows the Nucleus Accumbens Core (NAc) and Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) involved in the decision-making process. Image was created by tracing and using Microsoft PowerPoint.

A deep dive into decisions and dopamine

In this study, mice navigated a course with four zones, and each zone had a restaurant – a corner that dispensed different flavored food pellets. Different sounds indicated how long the mice had to wait to get the pellets, anywhere from 1 to 30 seconds. After repeatedly navigating the course, the mice learned to get the most food pellets in the shortest amount of time. Similar to how we make decisions, this task allowed mice to skip a zone or change their mind if the offer wasn’t valuable enough.

The scientists used dLight, a sensor that emits light whenever dopamine binds to it, to measure dopamine activity between the NAc and VTA regions during this decision-making task. They uncovered two groups of mice with different decision-making techniques. The “offer sensitive” group used an economically favorable technique. This meant that they avoided long wait times for a pellet, unless it was a flavor they preferred. They also considered the consequences of their selection. This forethought gave them more confidence so their decision to skip certain zones or change their minds maximized their ability to get the desirable flavors. The “offer insensitive” mice used a different strategy. Though this group also had preferred flavors, their decision-making technique was economically unfavorable. Since they did not use forethought like the other group, they waited a long time for any flavor, and often abandoned a zone after already investing a lot of time waiting on a pellet. Fascinatingly, each group had different patterns of dopamine signaling throughout the decision-making process.

The scientists became curious – if the two groups of mice had different dopamine activity during decision making, would changing this activity change their final decision? They used a technique called optogenetics to control the release of dopamine using light. While inhibiting the dopamine activity made the “offer sensitive” mice lose confidence in their decision and change their minds more, increasing this activity increased their confidence and made them change their minds less. Surprisingly, there was no change in the “offer insensitive” mice. Since the dopamine activity in these areas reflects the consequences of and the confidence in a decision, changing its activity only influenced the mice that used these techniques to come to their decisions, the “offer sensitive” group.

What does it all mean?

Can a change in dopamine in the NAc and VTA regions spark a change of mind? Yes, but only if you already have an economically favorable decision-making process like the “offer sensitive” group. Though dopamine can’t make us all better decision makers, this study brings us closer to understanding differences in how brains interpret information and differences in decision-making strategies that may exist in conditions like depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (1-2). Understanding why some groups have different levels of dopamine is also extremely valuable as it could help uncover causes and treatments for diseases where dopamine is a factor like Parkinson’s (3). On top of all that, stress can change dopamine release in the NAc and VTA regions (4), which we now know can change decisions in a certain group. With endless stressors in everyday life, it’s important to figure out how stress affects dopamine and decision making. All of these important areas can benefit from the foundational work described in this paper.

Additional References

- Mukherjee D, Lee S, Kazinka R, D Satterthwaite T, Kable JW. (2020) Multiple Facets of Value-Based Decision Making in Major Depressive Disorder. Scientific Reports. Feb 25;10(1):3415. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60230-z. PMID: 32099062; PMCID: PMC7042239.

- Chachar AS, Shaikh MY. (2024) Decision-making and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: neuroeconomic perspective. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Oct 23;18:1339825. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2024.1339825. PMID: 39507803; PMCID: PMC11538996.

- Hou G, Hao M, Duan J, Han MH. (2024) The Formation and Function of the VTA Dopamine System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Mar 30;25(7):3875. doi: 10.3390/ijms25073875. PMID: 38612683; PMCID: PMC11011984.

- Baik JH. (2020) Stress and the dopaminergic reward system. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. Dec;52(12):1879-1890. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00532-4. Epub 2020 Dec 1. PMID: 33257725; PMCID: PMC8080624.