Reference: Calmette, T., Calmette, T., & Meunier, H. (2025). Persistence suggests metacognition in capuchin monkeys. Animal Behaviour, 219, 123008.

Humans have the curious and amazing ability to not only have a thought, but to think about that thought itself. We self-monitor our generalizations, plan based on past mistakes, and reflect on our own thought processes.

We’re not just creatures that know; we’re creatures who know that we know. In other words, we are capable of metacognition, commonly defined as the awareness of one’s own mental states. This ability is central to developing self-awareness. Humans aren’t alone in this capacity; other primates, notably chimpanzees (1), show metacognitive abilities. Since metacognition is so important for human cognitive processing, understanding which animals can also use metacognition is key in revealing how this ability evolved.

Now, scientists have discovered that capuchin monkeys might possess metacognitive skills as well.

How Do Scientists Test Metacognition in Monkeys?

Earlier this year, Tony Calmette and colleagues devised a clever experiment with 11 capuchin participants to test whether they would search for a treat more persistently if they expected it to be present.

First came a pre-test phase ensuring that the capuchins understood the task. A researcher placed two opaque wooden boxes in front of each participant and, in full view, hid a piece of walnut in only one of them. Capuchins pointed toward the one box that they wanted to explore. If correct, they retrieved the walnut prize. If not, they received no reward.

In thetest phase, the same opaque boxes were used, but this time the researcher briefly obscured them – either for 5 seconds or 20 seconds – after hiding the walnut.

This served two purposes. First, it required the capuchins to rely on their memory of where the walnut was. Second, it allowed the researcher to secretly remove the walnut from the baited box. After this concealment, the capuchins again pointed to the box that they wanted to search, even though both boxes were empty.

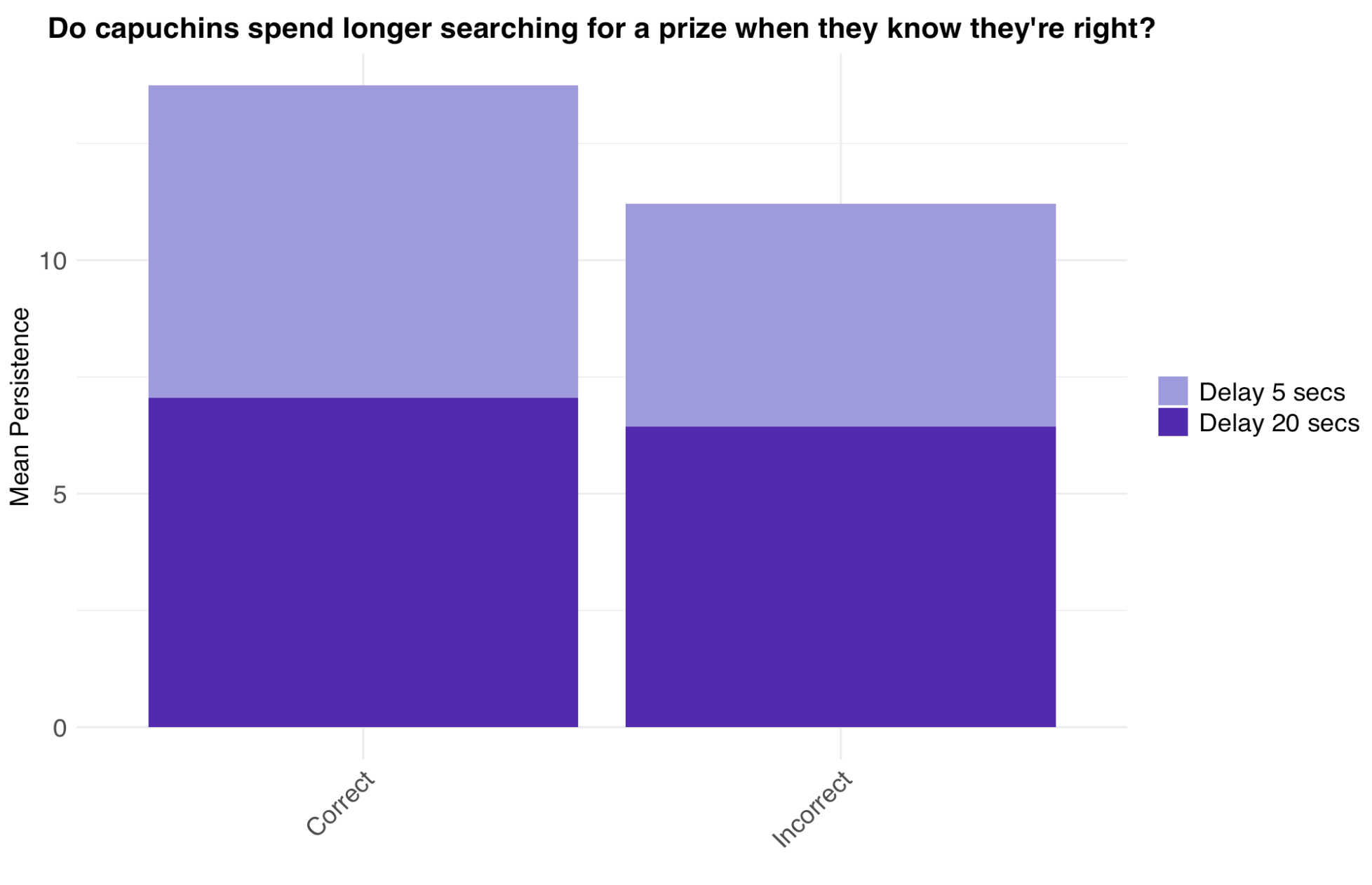

Researchers then measured persistence time – the total time the capuchin spent with its hand in the box searching unsuccessfully for the treat.

Regardless of search outcome, capuchins who originally selected the correct box were later given a piece of walnut to prevent frustration with the task.

Can Capuchins Remember the Right Box? Did Different Delay Times Impact Results?

Capuchins were more accurate when the delay was 5 seconds rather than 20, which makes sense – shorter delays make remembering easier. However, choice accuracy remained above chance at both time delays, showing that the capuchins understood the task and remembered the correct box more often than would be expected randomly.

Do Capuchins Search Longer When They Think They’re Right?

To answer the central question of the study – whether capuchins show metacognitive awareness – the researchers compared persistence time across trials. Capuchins who selected the correct box persisted for longer than those who chose incorrectly. Much like a human searching more diligently for a treat they know was placed somewhere, capuchins appeared to modulate their search effort based on their own expectations – evidence consistent with metacognitive processing.

Two capuchins bucked the trend, however. One selected the unbaited box only once, so the results for persistence were not particularly useful for this individual. The other, the youngest in the group, responded randomly, perhaps due to his young age and lack of task understanding. These exceptions raise interesting questions about how metacognition may develop in primate brains.

Rethinking Self-Awareness Tests in Animals

Mirror-spot tests, in which animals are marked with a dot and given a mirror to view themselves, have long been the gold standard for assessing self-awareness in animals. Capuchins usually fail these tests (2) which has led us to assume they aren’t self-aware. The persistence-based method used here offers a promising new way to evaluate self-awareness in species that don’t perform well on mirror tests.

So, are capuchins capable of metacognition? This study suggests the answer might be yes. Whether they are self-aware in the same way as humans remains an open question, but this study represents an important step toward understanding the breadth of advanced cognition in the animal kingdom.

Additional References

(1) Rosati, A. G., Felsche, E., Cole, M. F., Atencia, R., & Rukundo, J. (2024). Flexible information-seeking in chimpanzees. Cognition, 251, 105898. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2024.105898. Epub 2024 Jul 25.

(2) Roma, P. G., Silberberg, A., Huntsberry, M. E., Christensen, C. J., Ruggiero, A. M., & Suomi, S. J. (2007). Mark tests for mirror self-recognition in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) trained to touch marks. American journal of primatology, 69(9), 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20404

[…] is also a Cogbites contributor. You may have read her article on capuchin monkey metacognition, and she’s currently working on a new piece exploring how environmental surprise shapes prosocial […]

LikeLike