Reference: Borodovitsyna, O., Flamini, M. D. & Chandler, D. J. Acute stress persistently alters locus coeruleus function and anxiety-like behavior in adolescent rats. Neuroscience 373, 7–19 (2018).

Most people remember adolescence less than fondly as a time of embarrassing junior high dances and growing pains. While it may be that awkward phase between childhood and adulthood, adolescence is also a critical developmental window associated with a host of changes throughout the body. Hormones begin to run wild and remodeling occurs in many areas of the brain. Importantly, some of these changes may lead to increased sensitivity to stress, influencing mental health diagnoses such as depression and anxiety, which commonly arise during adolescence (1,2). Understanding why the adolescent brain is so sensitive to stress could help unravel the relationship between stress and adolescent mental health. This question has been the subject of research in the Chandler lab at Rowan University, where scientists are asking how adolescent stress may influence neuronal activity, specifically in the locus coeruleus (LC).

The Locus Coeruleus (LC) Responds to Stress

The LC (shown below) sits deep in the brainstem and is responsible for many cognitive and behavioral responses to stress. The LC is the main source of norepinephrine (aka noradrenaline) in the brain, which it uses to communicate to forebrain areas involved in executive function. Norepinephrine is a neurotransmitter released by the LC that helps control aspects of cognition like arousal, attention, and memory retrieval (3). Normally, exposure to stressful stimuli transiently increases LC activity, stimulating norepinephrine release which increases arousal level- typically a helpful feature when you’re faced with some sort of threat.

Importantly, trauma or stress may create imbalance within LC signaling, which can have dire consequences. For example, previous research using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown that the LC plays a role in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). MRI uses magnetic scanning to measure the oxygenation in brain tissue as a readout of neural activity, as more active tissues require more oxygen (4) (see previous post for more information https://cogbites.org/2019/07/22/what-is-fmri/). Increased startle response in PTSD patients was linked to higher LC activity in MRI scans, leading researchers to conclude that the LC may be responsible for symptoms of hyperresponsiveness seen in PTSD patients (5). Similarly, as the Chandler lab has demonstrated, the LC may be acutely sensitive to stress during adolescence, with lasting behavioral and physiological consequences.

Combining Behavior and Neuronal Recordings to Understand the LC

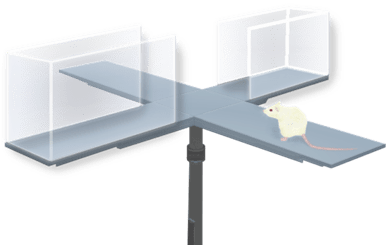

To assess how adolescent stress alters LC activity, the Chandler lab exposed male rats to physical restraint stress during adolescence (about 5 weeks old in rat years). In this 15-minute stressor, the rodents are placed in a plastic tube to restrict their movement while being exposed to a fox-based odor, simulating inability to escape a nearby predator. Control subjects were handled by the experimenter without exposure to any stressful stimuli. Following stress or handling, animals were immediately assessed for anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze. In this commonly used behavioral test, rodents are placed in a plus shaped platform with two open arms containing just a bottom walkway and two sheltered arms with tall side walls (see image below). Being naturally explorative, rodents usually venture into the open arms. However, when experiencing some threat or anxiety, rodents tend to remain sheltered in the safety of the closed arms. Time spent in the open versus closed arms can therefore serve as a measure of anxiety-like behavior.

After this test, the activity of LC neurons was recorded using electrophysiology. As excitable cells, neurons rely on the flow of small ions across their cellular membrane. This flow of ions generates electrical potential that can build up and eventually result in formation of an action potential. Action potentials are the electrical method of communication between neurons. This signal will travel from cell to cell and stimulate the release of neurotransmitters (such as norepinephrine) and other molecules to influence neuronal activity. Electrophysiology takes advantage of this neuronal property through use of electrodes placed on or within a cell which record changes in the cell’s electrical environment – a direct measure of neuronal activity (6). In this study, electrophysiological recordings were taken from some animals on the same day as the stressful event, and from others one week after the stressful event to temporally compare stress-induced changes in LC activity.

Chronic Changes in LC Activity

As expected, the stressed animals spent less time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze immediately after exposure to this adolescent stress, demonstrating anxiety-like behavior. This behavior corresponded to an increase in spontaneous LC activity (meaning these cells are firing more action potentials in response to stress) when compared to non-stressed controls. More unexpected were the lasting consequences seen one week after exposure to this single stressful event.

One week after stress, when compared to non-stressed controls, stressed animals displayed anxiety as well as a persistently hyperactive LC, suggesting their LC was still responding as if a stressful event had just occurred. Additionally, these cells were more excitable a week after stress, meaning they had increased likelihood of firing an action potential. The anxiety observed in these animals may be a direct consequence of this LC hyperactivity, which could be inducing above normal levels of arousal, similar to what was observed in the PTSD patients from the aforementioned clinical study.

The finding that a single stressful or traumatic event during adolescence can chronically alter behavior and LC activity has important implications for addressing PTSD, anxiety, and other mood disorders in adolescent populations. Importantly, other research suggests this LC response may be specific to adolescence (7). These outcomes mean that the same stressor may have distinct cognitive consequences when experienced during adolescence versus adulthood. Although the exact mechanisms responsible for this stress response in the adolescent LC are yet to be discovered, this research is an important step forward in identifying specific vulnerabilities within the developing brain, and their lasting impacts later into adulthood.

Additional References

1. Eiland, L. & Romeo, R. D. Stress and the developing adolescent brain. Neuroscience 249, 162–171 (2013).

2. Spear, L. P. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 24, 417–463 (2000).

3. Herat, L. Y., Schlaich, M. P. & Matthews, V. B. Sympathetic stimulation with norepinephrine may come at a cost. Neural Regen Res 14, 977–978 (2019).

4. Gore JC. Principles and practice of functional MRI of the human brain. J Clin Invest.112(1), 4-9 (2003). doi: 10.1172/JCI19010.

5. Naegeli, C. et al. Locus Coeruleus Activity Mediates Hyperresponsiveness in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biological Psychiatry 83, 254–262 (2018).

6. Neuronal electrophysiology: the study of excitable cells. https://www.scientifica.uk.com/learning-zone/neuronal-electrophysiology-the-study-of-excitable-cells.

7. Bingham, B. et al. Early Adolescence as a Critical Window During Which Social Stress Distinctly Alters Behavior and Brain Norepinephrine Activity. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 896–909 (2011).

Cover image from Monstera Production, taken from Pexels.

LC image adapted from: Patrick J. Lynch; illustrator; C. Carl Jaffe; MD; cardiologist Yale University Center for Advanced Instructional Media Medical Illustrations by Patrick Lynch, under Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License 2006.

Elevated Plus Maze graphic from: DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS), under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License 2021.